The disastrous flood of 1824, vividly described in Alexander Pushkin’s The Bronze Horseman, carried away or damaged a great many of the city’s timber bridges. This necessitated the construction of several new cast-iron and masonry spans in the late 1820s and the 1830s.

An interesting conglomeration of bridges designed by P. Bazaine, E. Adam and G. Traitteur, professors of the St. Petersburg Institute of Ways of Communication Engineering, was built on the upper Moika, at points between the Engineers’ Castle and the Palace Square. Beautiful metal railings and lamp-posts of meticulous workmanship were installed on each. The arches of these cast-iron bridges were embellished with decorative plates and cantilevers, also of iron casting. A survey of the Moika’s bridges is best begun from the spot where the river parts with the Fontanka near the Engineers’ Castle.

In the course of the 1820s C. Rossi, an eminent Russian architect, laid out quays along the Fontanka and Moika to accommodate pedestrian and vehicular traffic, extended Sadovaya Street all the way to the Field of Mars, and selected sites for new bridges over the two rivers.

The St. Panteleimon’s Bridge over the Fontanka, built in 1823 by G. Traitteur and V. Christianovich, was Russia’s first suspension bridge open for the vehicular traffic. It had a roadway suspended from five wrought-iron chains that passed over two iron pylons and were securely anchored at both ends. Between 1825 and 1837 several cast-iron and masonry bridges designed by P. Bazaine were built over the Moika and the Swan and Voskresensky (Resurrection) canals near the Engineers’ Castle, the Voskresensky just south of the castle, at the time.

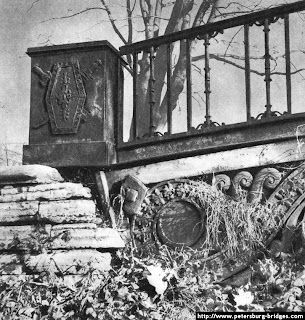

The end of the 1820s saw the completion of the First Engineers’ Bridge, which spanned the Moika close to where it branches off from the Fontanka. Its arched span was constructed of cast-iron “box” blocks. Light was provided by torcheres shaped to resemble bundles of spears, and the railing was embellished with plaques depicting crossed swords and shields decorated with the head of the mythical Gorgon Medusa. The arches were adorned with iron castings representing shields, helmets and other items of a warrior’s armour.

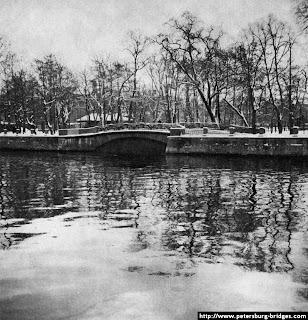

At the south-east corner of the Engineers’ Castle the granite quay of the Fontanka’s right bank is interrupted by the rather unusual Second Engineers’ Bridge, – a bridge over dry land. This bridge, built in 1830, used to span the Voskresensky Canal, since filled up. The bridge with its handsome railing was spared, however.

Much the same is the story of another bridge, the one that spans a dried-up watercourse next to the pond of the Mikhailovsky Garden. Built also around 1830, it spanned a creek that connected the pond with the Voskresensky Canal mentioned above. In the mid-1830s two more masonry bridges were built in the vicinity of the Engineers’ Castle, both designed by P. Bazaine.

One, now known as the First Garden Bridge, carried Sadovaya (Garden) Street over the Moika (in 1907-8 its masonry arch was replaced by one of steel); the other, called the Lower Swan Bridge, spanned the Swan Canal. Stylized Roman weapons are the motif of the railing and the lamp-posts of both these bridges.

Their architectural design was possibly worked out by C. Rossi. The St. Panteleimon’s suspension bridge remained in service for eighty-five years. In 1908 the risk of its collapse under the weight of ever heavier traffic caused it to be taken down and replaced with an arch bridge of steel, designed by A. Pshenitsky and L. Ilyin.

To avoid any conflict with its architectural entourage Ilyin introduced into its decor the same motifs, such as spears, shields, etc., that had been used in decorating the neighbouring bridges over the Moika, built in the nineteenth century. In 1967 the so-called Second Garden Bridge, with a span of modern reinforced-concrete construction, was built at the south-west corner of the Field of Mars. Its designers, E. Boltunova and L. Noskov, wished to unite it with the general scheme of the Field of Mars, which included the building of the former

Paul’s Guards Regiment barracks and the former Imperial stables built by V. Stasov, an outstanding Russian architect; and the lamp-posts for the new bridge were accordingly copied from those of the First Garden Bridge, while the railings repeated the pattern of those of a bridge now no longer extant, which had spanned the small river (since filled up) at the Narva Triumphal Gate and had been designed, possibly, also by V. Stasov.

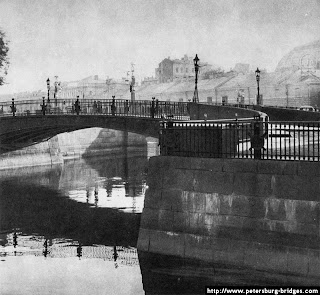

A bit farther downstream from the Second Garden Bridge, where the Griboyedov Canal flows out of the Moika, stands one of old St. Petersburg’s architecturally most interesting bridges. It is composed, as it were, of three parts; the single-span Malo-Koniu-shenny (Small Stables) Bridge over the Moika, the similarly single-span Theatre Bridge over the Griboyedov Canal where it Jssues from the Moika, and a third, “false” bridge.

The latter’s decorative cast-iron arch creates together with the load-bearing arch of the Theatre Bridge a strictly symmetrical composition that completes very appropriately the panorama of the Griboyedov Canal. This unique structure and its arresting architectural decor were worked out by G. Traitteur after the introduction of some minor modifications into the initial project drawn up by E. Adam.

Somewhat earlier (in 1828) E. Adam and G. Traitteur had designed and built the Great Koniushenny Bridge over the Moika on the far side of the former Imperial stables.

Across from the building of the Kapelle the Moika is spanned by the wide Kapelle (Pevchesky) Bridge, built between 1838 and 1840. Like the Red Bridge, it has kept its old railings separating the footwalks from the roadway, though of greater interest is the outer railing – a masterpiece of cast-iron lace-work of beautiful design and meticulous craftsmanship. Both the architecture and decor of the Kapelle Bridge are the work of E. Adam.

The Moika bridges built in the first half of the nineteenth century rightly rank among the outstanding achievements of Russian architecture. Identical in construction (their arches are assembled of cast-iron “box” blocks), their exterior almost always carries some individual traits “Among our capital’s bridges,” wrote V. Kurbatov, a great authority on St. Petersburg’s architecture, “there are some that should figure prominently in the general history of art… We should be proud of them.”

An on-line compilation of a photographic study of the bridges in Leningrad (the former name of Saint Petersburg), published by Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1975.

Эта страница доступна на Русском языке.