The art of the archaic and early classical periods, 800-450 B.C. The oldest examples of Greek art in the exhibition are some ninth – eighth century clay vessels with geometric patterns painted in black or reddish brown pigment.

This ornamental pattern, consisting of circular bands, sometimes includes geometric representations of animals, birds and man. The vessels of the geometric style, like the primitive statuettes of bronze and clay, belong to the era of the tribal system and the birth of the slave-owning city-states, the so-called poleis. During the seventh and sixth centuries can be observed the rapid growth of the Greek poleis of Miletus, Clasomenus (Asia Minor), Rhodes, Chios, Samos, Athens, Corinth, etc. Busy trade connections were established between them, and trade was likewise developed with the countries of the East. Among the crafts, pottery was the most important. The Corinthian vases of the “carpet’ style, the decorative patterns of which bring to mind an eastern fabric, were famous throughout the Mediterranean in the seventh and sixth centuries B. C. (cabinet 2). In Athens, one of the most prominent centres of Greek crafts, trade and culture, the so-called black-figure style was prevalent in the sixth century. Upon the orange-coloured surface of the clay vessel a black silhouette was drawn, and the details were scratched in with a chisel and painted in purple and white pigment. These black-figure vessels are extremely decorative, and the shining black pigment, often called lacquer, stands out boldly against the colour of natural clay beneath a transparent glaze (cabinets 7 and 8). Towards the end of the sixth century B.C. and the beginning of the fifth, the black-figure style was replaced by the red-figure style. Now the ground was covered with lustrous black pigment, and the figures were composed in the natural terra-cotta tones of the clay, all the details painted by brush or quill. This method made it possible to render more vividly and convincingly the multifigured compositions of mythological, epic and genre scenes which usually adorn the surface of Attic vessels. Some vases have preserved the names of their creators; a wine bowl bears the inscriptions Made by Hischylus and Painted by Epictetus. Upon a psykter, decorated with the figures of hetaerae reclining on couches, there is the inscription Painted by Euphronios. The Hermitage example is one of a group of vessels that have been preserved bearing the signature of this celebrated Greek craftsman of the late sixth – early fifth centuries B.C. Also attributed to Euphronios is the famous “Vase with a Swallow” (case 12). On one vase there is the curious inscription, Painted by Euphimides, son of Polios like Euphronios could never do!

Greek ceramics are extremely varied in shape; there are ampho-ras-tall vessels with two handles for storing or carrying wine and oil- squat, three-handled hydrias for water; kraters for mixing wine with water; drinking cups – ky.ices, kanthari and ^yph’iand vessels used for storing fragrant oil – narrow-necked lecythi, globe-shaped aryballi, and slender alabastra. Ancient Greek ceramics were famous far beyond the frontiers of Greece and were w.dely exported.

The small-size bronze sculpture of the sixth and early fifth centuries, including statuettes of youths and a stand for a mirror in the form of the goddess Aphrodite, introduces us to the archaic style in sculpture. The figures are static and are portrayed en face, with characteristically prominent eyes, and the hair and the folds in the clothes are represented schematically (cabinet 3, cases 5 and 9).

The statue of Hyacinth, attributed to Pythagoras of Rhegium, is evidence of the realist features of Greek art in the first half of the fifth century B.C. The famous sculptor gave the lean, supple body of the youth spatial life. Hyacinth is portrayed watching the flight of the discus with intence interest.

Room 112. The art of the Golden Age (500-400 B.C.). The basic theme of the classical period is the portrayal of the athlete, the victor ludorum, the bold, valiant defender of his native town, as well as the representation of the gods who personified the wealth and power of the state. The most eminent Greek sculptors during the Golden Age were Myron, Polycletus, and Phidias. Myron, who worked in bronze and whose work survived only in Roman copies, was the creator of the famous statue Discobolus. Similar in style to the works of Myron are the statues of a woman (No. 95), of the god of healing Aesculapius (No. 94), and also the head of a fist-fighter (No. 143) displayed in room 113.

The basalt head of a youth (No. 140) with a classically regular, tranquil face belongs to the sculpture of Polycletus’ circle. It recreates the celebrated Doryphoros (The Spear-bearer) done by Polycletus in strict conformity with his Canon, a tractate on the proportions of the human body. Polycletus, like Myron, worked in bronze, but his originals have not been preserved. Other works of the same circle are the torso of an athlete (No. 104a) and the statue of Hermes (No. 104).

The name of Phidias is associated with the imposing architectural and sculptural ensemble of the Acropolis in Athens, In this city, which in the fifth century B.C. as a result of the victory of democracy became the political and cultural centre of all Greece, was erected the marble temple of the Parthenon in honour of the protectress of the city, the goddess Athena. The temple was adorned with a statue, twelve metres in height (over 37 ft.), of Athena Par-thenos (Athena the Virgin); her clothes and armaments were made of gold, the face and hands of ivory. The works of Phidias have not survived to our time, and so of special value is the embossed representation of the head of Phidias’ Athene, made by an unknown fourth century Greek jeweller, on gold pendants which were found in the Kul-Oba burial-mound and are now kept in the Gold Room of the Hermitage. The Roman copy of a fifth century marble statue gives us some idea of Phidias’ style; the warrior goddess is portrayed in a calm, majestic pose, leaning against a spear (No. 98), the head of Athena is crowned with a helmet, and the dress, descending in a series of folds, emphasizes the magnitude of the frontally portrayed figure. This representation personified the unshakable power of the Athenian state. Two stelae, the tombstones of Philost-rata and Theodotus (Greek originals), give us some idea of the classical relief at the time of Phidias.

Heracles Slaying the Lion of Nemea. 1st-2nd century Roman copy of iysippus’ original

Heracles Slaying the Lion of Nemea. 1st-2nd century Roman copy of iysippus’ originalThe Resting Satyr. 1st-2nd century Roman copy of Praxiteles’ original

Room 114. Greek art, 400-300 B.C. The complex social and political situation in Greece during the fourth century B.C. brought about the development in art of several trends, of which Scopas, Praxiteles and Lysippus are good representatives. These great sculptors, differing enormously in their creative individuality, are united by their interest in man’s inner world; their portraits of the gods are even more “human” than was the case in the fifth century B.C. Several sculptures in the exhibition are from the school of Scopas (his work has survived only in Roman copies); one of these is the statue of Heracles (No. 272). The hero’s muscular body appears tired, and the deeply sunken eyes and the mouth half-open in suffering lends a mournful expression to his face. The fervour of passions – suffering, ecstasy, fury – is the basic theme of Scopas’ work.

His contemporary, Praxiteles, worked mainly in marble. Praxiteles’ heroes are usually portrayed in some light reverie, and in poses full of indolent grace. The smoothly outlined figures are notable for their proportions, elongated in comparison with Polycletus Canon. Acquainting the visitor with the work of the great sculptor is a whole series of items: The Resting Satyr, a copy of one of the sculptures by Praxiteles most popular in antiquity; the head of Aphrodite (No. 300), similar to the type of the celebrated Aphrodite of Cnidus; Satyr Pouring Wine, a copy of one of Praxiteles’ early works, and others. The portrait of the Greek dramatist Menander was executed by Praxiteles’ sons, Cephisodotus and Timarchus.

The small marble group called Heracles Slaying the Lion of Nemea is a reduced-size copy of a bronze sculpture by Lysippus from a series devoted to the twelve labours of Heracles. Lysippus was a master of sculpture in the round. The powerful figure of Heracles and the body of the beast are represented in such a way that the group can be viewed from all angles. The sculptor depicts the climax of the duel between man and beast; Heracles is strangling the lion, which, as its strength is sapped, sinks down onto its hind paws. The extent of Lysippus’ creative scope can be seen from his Eros Stringing the Bow and the statuette The Feasting Heracles. He also worked in the field of portraiture, and the head of the great Greek philosopher Socrates was based upon Lysippus’ original. His work crowned the achievements of Greek art of the fifth and fourth centuries B. C.

Room 121. The Hellenistic period is the traditional name for the era beginning with the conquests of Alexander the Great and ending with the Roman conquest of Egypt. On the lands of the Hellenistic states (Egypt, the kingdom of the Seleucidae, the kingdom of Pergamum, etc.) there grew up several schools of art, the foremost of which were in Alexandria, Pergamum and Rhodes.

Nowadays we have only isolated examples of original works of Greek marble sculpture, whereas much terra-cotta has been preserved. Elegant terra-cotta statuettes were made in many cities in Greece, Asia Minor and the northern Black Sea coastlands, though particularly highly esteemed were the items produced in the Greek town of Tanagra, whose craftsmen were influenced by the work of Praxiteles. The Hermitage collection of Tanagra terra-cottas of the fourth and third centuries B.C. ranks among the finest in the world (cases 3-6). The figurines of girls, youths and children in the costume of that time provide interesting material for studying the Greek way of life. Frequently terra-cottas reproduce in miniature famous statues of antiquity which have not come down to the present day.

In almost all the rooms of the department devoted to the art of antiquity there are displays of gems – carved stones, which were no less prevalent in the world of antiquity than in the countries of the ancient East. Carving on precious and semi-precious stone was done by hand and on the lathe, which was known in Greece as early as the sixth century B.C. The Hermitage collection includes hundreds of specimens of beautiful intaglios and cameos. The former were known in the Hellenistic period among the aristocracy, who surrounded themselves with luxury previously unheard of. Cameos were inserted into diadems, fibulae and rings, they were used to embellish valuable vessels, or simply preserved as works of art. In one of the horizontal cases by the window is the Gonzaga Cameo, exceptionally beautiful and among the largest of its kind (15.7 X 11.8 cm. – 6.14×4.65 in.). On a three-layered sardonyx, almost transparent and fancifully coloured by nature, two exquisite profiles were carved in high relief,- the Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemy Phila-delphus and his wife Arsinoe. The Gonzaga Cameo was made in the third century B.C. in Alexandria, the capital of Ptolemaic Egypt and one of the leading centres of Hellenistic culture. The Alexandrian school, in which genre themes in particular were widely developed, frequently treated with naturalistic details, is represented in the exhibition by some characteristic examples: The Satyr with a Splinter and Shepherd with a Lamb. Such marbles were traditionally placed in the corners of gardens. In this room should be noticed three items representing the school of Pergamum which was influenced by Scopas: the heads of a dying Gaul (No. 501), a dying giant (No. 21a) and of the dead Patroclus (No. 75)-and also moulded copies of the sculptural frieze from the Altar of Pergamum (room 105). From the Rhodes school is the fragment of a statue,- the head of a dying companion of Odysseus (No. 86).

Rooms 108 and 109. Graeco-Roman decorative sculpture. The architecture of room 108, completed about 1851 by the architect Yefimov according to Leo Klentze’s design, reproduced the inner courtyard of a grandiose Hellenistic or Roman house.

The fountain with the statue of Aura, the goddess of the air and the gentle breeze, and some examples of decorative sculpture – Eros Holding a Shell, The Infant Heracles Strangling the Snakes and Boy with a Bird – at one time adorned similar courtyards and rooms in ancient houses. The realistic portrayal of the child was one of the most significant achievements of the art of the Hellenistic period.

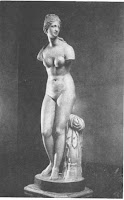

Room 109 contains a wonderful collection of marbles which decorated palaces, villas, gardens and parks during Hellenistic and Roman times; these include statues of Dionysus, Aphrodite, dancing satyrs, and figures of the Muses. Of wide renown is the statue of the goddess of love and beauty Aphrodite, later called the Venus of Tauris after the Tauride (Tavrichesky) Palace in St Petersburg, where it was kept from the end of the eighteenth century until the mid-nineteenth. An unknown craftsman of the third century B. C, inspired by the conception of the Aphrodite of Cnidus, portrayed the beautiful goddess nude; her well-proportioned body is more fragile, her beauty more refined than that of Praxiteles’ goddess. The Venus of Tauris, ceded to Peter the Great by Pope Clement XI after protracted diplomatic negotiations, was, in 1720, the first antique statue to appear in Russia.