The exhibition of Italian art occupies over thirty rooms. All the important Italian schools of art are represented by works of the most eminent exponents of painting and sculpture, and also by items of applied art.

Italy was the first European country to set foot upon the path of progressive social and cultural achievement. In Italian cities, amid the fierce struggle against the medieval, feudal way of life, a new bourgeois culture developed. It was distinguished by its secular, optimistic character and was imbued with a belief in the reason and potentiality of man. Both literature and art reached a high peak. This new stage in the development of Western European culture became known as the age of the Renaissance.

Room 207. The art of the 13th – 14th centuries. The first room in the exhibition contains works of art created in different Italian towns. The earliest of these is the Crucifixion by the Pisan artist Ugolino da Tedici, a very rare example of the painting of the second half of the thirteenth century. The fourteenth century devotional images, painted on wooden panels in tempera, are notable for their bright colours and the abundance of gold. One such image, the work of an unknown fourteenth century artist, is the Madonna and Saints. The Madonna, seated on a throne, is represented as the heavenly queen; her face wears a majestic, austere expression, and around her head is a halo. The Madonna’s position of supremacy is emphasized by the fact that she is placed in the centre of the composition and considerably exceeds in size the figures of the saints standing beside her. The finest item in the room is the work of one of the foremost Italian artists of the fourteenth century, Simone Martini (1283-1344), who hailed from Siena. This depicts the Madonna in a scene from the Annunciation, when she humbly listens to the word of the angel. The lithe, elongated figure of the Madonna, smoothly wrapped in a blue cloak reaching down to the ground, stands out sharply against a gold background. Finely executed, and beautiful in its colours, the painting has an unusual poetic quality.

The exhibition includes a number of works by the Florentine artists Spinello Aretino, Lorenzo da Niccolo Gerini and Antonio Fi-renze. In rooms 208-216 is represented chiefly the Florentine school of painting, which in the fifteenth century assumed the leading role among the Italian schools of art. In rooms situated parallel to these (217-222) are examples of the art of another important school, the Venetian.

Rooms 208-213. The fifteenth century, the so-called Early Renaissance, was marked by persistent quests and important discoveries in several different spheres. Artists worked out the laws of perspective, developed the theory of the proportions of the human body, acquired new methods of composition and studied the legacy of antiquity. In their works they strove to convey the richness of the world around them, making man the focal point of interest. Religious subjects, so common in the Middle Ages, continued to exist, but they were treated in the manner of secular scenes and filled with another, profoundly human content. Moving through the exhibition from the devotional images of the fourteenth century to the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci, it is easy to observe the fundamental progress in art, which was moving towards a mastery of actual reality.

Room 209. The fresco entitled Madonna and Child with St Dominic and St Thomas Aquinas was painted at the beginning of the 1440s on the refectory wall in the monastery of San Domenico in the township of Fiesole near Florence, by the artist and monk Fra Beato Angelico da Fiesole, (1387-1455), and is a good example of how in art the old is replaced by the new. The figures have acquired a three-dimensional quality, the faces have an individuality of their own, and the gold background has been replaced by a blue sky. Skilfully represented is the gossamery fabric of the cloak falling from the shoulder of the Madonna, whose whole appearance is filled with tranquility, contemplation and a gentle beauty.

The Vision of St Augustine acquaints us with the work of the famous fifteenth century Florentine painter, Filippo Lippi (1406- 1469). Taking a religious theme, the artist depicted his figures against a landscape background, using methods of linear perspective. The new view of man in the age of the Renaissance brought about the appearance of the realistic portrait. Interesting in this respect is the bronze bust of an unknown man by Sperandio Savelli (1425- 1495), and similarly the terra-cotta Portrait of a Florentine Man by Benedetto da Maiano (1442-1497), exhibited in room 210 where fifteenth century Florentine sculpture is displayed. Among these items is the Nativity (majolica) by Giovanni Delia Robbia (1469-1529). This is notable for the narrative character typical of the Early Renaissance, and resembles an everyday scene from Italian village life portrayed with a lively spontaneity. The development of the use of majolica is connected with the studio of the famous Florentine sculptor, Luca Delia Robbia (1400-1481). In this same room is a terra-cotta bust of his entitled the Infant John the Baptist. Luca Delia Robbia first used majolica -an inexpensive, but attractive material- on a large scale as a way of embellishing architecture (see on the walls the medallions bearing figures in relief). The work of the leading sculptors of the Florentine Renaissance, Antonio Ros-sellino and Mino da Fiesole, is represented by marble reliefs depicting the Madonna and Child (rooms 211 and 212).

Room 212. Filled with a joyful, jubilant mood, so characteristic of Renaissance art, is the Annunciation by the Venetian painter Cima de Conegliano (1459-1517). The scene is set in the room of an Italian house; outside the window stretches an urban landscape. In an attempt to produce an impression of earthly materiality in his painting, the artist fixes the attention of the observer not only upon the figures of the Madonna and the angel, but also upon individual details, for example a fly crawling across the paper. The Portrait of a Woman by the Ferrarese painter Lorenzo Costa (1460-1535) is a beautiful example of the half-length portrait, which was widespread in the fifteenth century. Among several works by the Bo-lognese artist Francesco Francia (1450-1517/18) the richly coloured Madonna and Child with St Lawrence, St Jerome and Two Angels is worthy of special note. The traditional solemnity is combined in this altar-painting with a convincing characterization of the figures.

In room 213 we should single out two late works, St Dominic and St Jerome, by Sandro Botticelli (1444/45-1510), who headed a group of artists at the court of the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de Medici the Magnificent. Also associated with this circle of artists was a pupil of Botticelli, the sophisticated Filippino Lippi (1457?-1504); among his works is one of the finest paintings in the Hermitage collection, the Adoration of the Child. Also here are St Sebastian and Portrait of a Young Man by the Umbrian Pietro Perugino, the teacher of Raphael. The Florentine sculptor Desiderio da Settignano (1428-1464) is represented by two marble heads of the infant Christ, executed in the “airy” style characteristic of the artist.

Room 214. The achievements of the fifteenth century are summed up in the work of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), which opened up a new era in the development of Italian art – the High Renaissance. Little over ten of the great master’s paintings have survived and these are dispersed among museums of different countries. There are two Leonardos in the Soviet Union, both housed in the Hermitage Museum.

The Benois Madonna, sometimes called the Madonna with a Flower, was painted about 1478. Rejecting the traditional representation of the Madonna, Leonardo created an exalted female figure full of terrestrial charm. The smiling, youthful Madonna, in the smart dress of a Florentine townswoman, is holding a flower in front of the child, watching the still uncertain movements of the boy who is reaching out for the petals. The mist (sfumato), typical of Leonardo’s work, lends the faces an unusual expressiveness. The sturdy, plump body of the boy, modelled as it were in chiaroscuro, is evidence of the fact that the discoveries of Leonardo the scientist aided Leonardo the artist; it was not without cause that he called painting a science, “the legitimate child of nature ‘. The theme of the glorification of man, of great emotions, is felt even more strongly in the Litta Madonna, which was painted around 1490. The sublime and poetic image combining physical and spiritual beauty embodies the Renaissance Ideal. Her eyes lowered, the Madonna is admiring the child lying in her arms; her face is beautiful and expressive, bearing the most subtle nuances of maternal feeling. Leonardo portrayed with wonderful skill the delicate body of the child, the golden ringlets of his hair and the intent gaze turned towards the spectator. The serene silhouette of the Madonna stands out boldly against the dark background of the wall; the bright openings of the windows, beyond which stretches a mountain landscape shrouded in a bluish haze, are placed symmetrically at each side and, balancing the composition, create an illusion of space. Because of the perfection of formal arrangement characteristic of the High Renaissance, this work of Leonardo evokes a feeling of tranquility, calm and harmony.

Among the works exhibited in room 215 of pupils and disciples of Leonardo-Andrea del Sarto, Cesare da Sesto, Bernardino Luini and Salaino – there is one painting which stands out in particular for its great artistic quality. This is the Portrait of a Woman, also known as Columbine or Flora, painted by Francesco Melzi, a young friend of Leonardo in whose arms, in France, the great master died. To a certain extent the head of the Parmesan school, Antonio Correggio (1494-1534), was also influenced by Leonardo; the Portrait of a Woman gives us some idea of his work. What takes the eye in room 216 is the profoundly dramatic Lamentation signed by Sebastiano del Piombo (1485-1547), a well-known artist who worked in Venice and Rome. Extremely typical of the art of the Renaissance is the Portrait of a Man by a Venetian artist of the first half of the sixteenth century, Domenico Mancini, who created the ideal image of the man of his epoch,-outwardly perfect, spiritually rich, and self-confident.

Already in the 1530s, in a copmlex social and political atmosphere, there sprang up in Florence, and then became widespread in other Italian cities and abroad, a movement known as Mannerism, which marked a departure from the humanistic traditions of Renaissance art. Among the leading representatives of this trend are, in painting, the Florentine artists Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1557) and Giovanni Battista Rosso (1494-1541); and in sculpture Giovanni da Bologna (1529-1608). Displayed in room 216 are a fountain sculpture and some small bronzes of his.

Room 229. Raphael Santi (1483-1520), in whose works the ideals of the High Renaissance received their most lucid expression, is represented in the Hermitage by two early works. The Conestabile Madonna was painted by Raphael between 1500 and 1502. The young mother is pensively looking at a book, to which the child is reaching out; the Madonna’s pure, lyrical appearance is echoed by a gentle spring landscape. In the Holy Family (1507) Raphael attained the majestic simplicity, clarity and harmony characteristic of the High Renaissance. The exalted figures of the Madonna and Joseph, stripped as it were of all incidental features, represent types rather than individuals. In one of his letters Raphael revealed the essence of his method of creation: “To paint a beautiful woman I should have to see a large number of beautiful women; but as there are few beautiful women and few true judges, I take as my guide a certain idea…” In the Holy Family the “type” of the ideal man, expressing the synthesis of individual characteristics taken from life as seen by the artist, corresponds to the humanistic conceptions (the “certain idea ‘ of the Renaissance emphasizing the great significance of the human personality.

In the centre of the room is the fountain sculpture entitled Dead Boy on a Dolphin created by one of the many pupils of Raphael, Lorenzo Lorenzetto, after a drawing of his teacher. The theme of the sculpture, borrowed from a classical legend, describes how a dolphin bore his dead young friend ashore.

Another pupil of Raphael, the famous artist and architect Giu-lio Romano, produced an enormous cartoon Procession with Elephants, which appeared as part of a series of twenty-two representing the feats of the ancient Roman military leader Scipio Afri-canus and his triumphal procession after his victory in the Second Punic War.

The Hermitage possesses a rare collection of sixteenth century Italian majolica from various centres – Faenza, Siena, Castel-Du-rante, Deruta, Gubbio and Urbino. The majority of these items are decorative vessels – vases, bowls, dishes – with brightly coloured painted designs based upon motifs from classical and biblical legends. Particular mention should be made of a collection of fifteenth and sixteenth century Italian furniture which was made chiefly from walnut, decorated with carving and in many cases painted and gilded. A typical item of furniture was the cassone, a coffer used for keeping part of a bride’s outfit. In their shape these coffers remind us of the sarcophagi of antiquity.

Room 227. Raphael’s loggias. The museum contains the only reproduction in the world in the original size of Raphael’s celebrated loggias, erected in the Vatican Palace by the architect Donato Bramante (1444-1514) and painted between 1516 and 1518 by pupils of Raphael after his sketches and under his supervision. The loggias form a high, well-lit gallery, the ceiling of which is decorated with fifty-two paintings based upon biblical stories interpreted in the spirit of the Renaissance. The walls are completely covered with paintings in which motifs from classical mythology are interwoven with plant designs and the representations of animals and birds. Serving as a model for the design of the loggias was the decorative ornamentation of the ancient Roman thermae of Titus and several other ancient edifices, the excavation work on which was led by Raphael. The Hermitage copy was made at the end of the eighteenth century by a group of artists under Christopher Unterberger. The work of copying was carried out in the Vatican over a period of seven years. Painted canvases brought from Italy were stretched out on frames and inserted into the walls of the Hermitage loggias, specially built for this purpose by Giacomo Quarenghi.

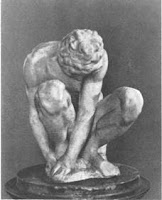

Room 230. The work of the great sculptor, painter and architect Michelangelo (1475-1564) is represented in the Soviet Union by one sculpture, the Crouching Boy, created in the early 1530s and belonging apparently to the sculptures which were intended to adorn the tomb of a Medici in Florence. The statue remained unfin-shed, but in spite of that, great inner strength is felt in the work. In this sence the figure is characteristic of the work of Michelangelo, who glorified in his creations the heroism and courage of Man the warrior, Man the creator. In the exhibition, among the small-scale sculptural work of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there are copies of famous masterpieces by the great sculptor – Pieta, Moses and Day. Into the walls of the room have been fitted some frescoes by artists of the Raphaelite school.

Displayed in room 219 is one of the great treasures of the Hermitage collection of Venetian painting, – Judith by Qiorgione (1478? – 1510), with whose work began the period of the High Renaissance in Venice. In his representation of the biblical heroine Judith, who slayed the enemy leader Holofernes, Giorgione created a noble, somewhat enigmatic in its restraint, but highly emotional and charming image of a young woman. Judith stands in a majestic pose, her sword lowered, her foot resting upon the severed head of her enemy. With Giorgione, as with all painters of the Venetian school, the use of colour played an important role in the creation of the artistic image. In 1968 the painting was restored; after the removal of the dirt and the varnish which had decomposed with age, Giorgione’s colours sparkled like gems.

Titian (1485/90-1576), the head of the Venetian school, began his creative work at the same time as Giorgione. The Flight into Egypt, one of his early works, is displayed in this room.

Room 221. With the exception of the Flight into Egypt (early 1500s), Titian is represented in the Hermitage by works from his mature period (Portrait of a Young Woman, c. 1530s; Danae, painted in the 1550s; Madonna and Child with Mary Magdalene, c. 1560; The Penitent Magdalene, 1560s; Christ Blessing, 1560s; Christ Carrying the Cross, or Christ and Simon of Cyrene, 1560; and St Sebastian, c. 1570). Each of these is a masterpiece ranking among the finest in the history of art. Danae was painted on the theme of the classical Greek myth in which Zeus, in the form of golden rain, visits his beloved, the princess Danae, who is imprisoned in a tower. The sparkling flow of coins falls upon Danae; at the feet of the beautiful princess sits an old servant-woman, and in the clouds can be seen the head of the grey-bearded Zeus. The painting is based upon the colour contrast of the nacre-pink body with the cold tone of the white sheet and the purple canopy of the bed. The perfect proportions of Danae’s naked body are evidence of Titian’s adoption of the classical ideal of beauty.

In the Penitent Magdalene the artist focuses attention not on the ascetic idea of the Christian legend, but on the figure of the sensually beautiful young woman. The world is beautiful, and man is the most perfect creation of Nature -such is the main idea behind this painting. The agitated state of the beautiful, golden-haired Magdalene is echoed in the landscape, with the summer lightning aglow in the dark blue, thundery sky and the solitary tree bending against the gusts of wind. Toward the end of his life, in connection with the general crisis in Renaissance culture, some tragic notes are sounded in Titian’s work. St Sebastian, painted by Titian at very advanced age, strikes the viewer with the strength of its dramatic effect and the amazing artistic skill, evidence of the inexhaustible creative energy of this great Venetian painter.

Room 222. Acquainting us with the work of Paolo Veronese (1528-1588), one of the most eminent Venetian painters of the second half of the sixteenth century, is a group of excellent pictures: the vivid, jubilant Adoration of the Magi; the Lamentation, dramatic in spirit and expressive in colour; Portrait of a Man; and Diana, a small sketch made for the decorative paintings of the Villa Maser near Vicenza.

In two small rooms adjoining room 222 there is a collection of Venetian glass and painted enamels on copper, Italian fabrics, and articles made of bronze and leather (fifteenth – seventeenth centuries).

Room 237. Side by side with Veronese’s painting the Conversion of Saul, dominated by a mood of perturbation and anxiety, in this room there is the only work of Jacopo Tintoretto (1518- 1594) in the Hermitage collection, The Birth of John the Baptist. In this painting the genre subject appears as a distinct form,- women are fussing around the new-born child, and their dresses, the decor of the room, the cat creeping towards the hen, and the brazier on the floor, all take the spectator into the atmosphere of a sixteenth century Venetian house.

The Hermitage has a very large collection of paintings by artists of the Bologna Academy, founded by the Carracci brothers in the 1580s. Coming out against Mannerism, the Bologna Academy evolved a strict system of art, its main principle being in the pursuit of an ideal of the beautiful, which the Bolognese looked for not in nature but in the world of ideas. Two canvases, Holy Women at the Sepulchre and Lamentation over the Dead Christ, introduce us to the work of the head of the Bologna Academy, Annibale Carracci (1560-1609). The prominent representatives of thes academic style were Quido Reni (Girlhood of the Virgin and St Joseph Holding the Infant Christ), Domenichino (Mary Magdalene’s Ascension into Heaven) and Quercino (The Martyrdom of St Catherine and The Assumption). A number of paintings by the artists mentioned here are to be found in room 231.

Lionello Spada (1576-1622), having studied at first under Annibale Carracci, later became a disciple of Caravaggio. The fierce dramatic effect of his Crucifixion of St Peter derives not so much from the subject itself as from his interpretation of it and from the use of sharp light and shade contrasts which he learned from Caravaggio.

Room 232. The Lute Player, the only painting in the Soviet Union by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1569-1609), the leading figure of seventeenth century Italian realism, belongs to the early period of the artist’s work. A young Italian, with a simple but expressive face, is pensively running his fingers over the strings of a lute. The brightly lit figure of the boy and the small accessories of still life – a vase filled with flowers, fruit, a violin and music- stand out against a dark background. Caravaggio’s work exercised great influence upon the development of realism, not only in Italian art but also abroad. It expressed the progressive tendencies in Italian art during the Baroque era (late sixteenth century to mid-eighteenth), which witnessed very diverse and contradictory artistic phenomena. The foremost artist of the Roman Baroque, the sculptor and architect Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), is represented by a Self-portrait in terra-cotta and by a splendid collection of terracotta bozzetti – small models for his monumental works. In the following room (233) is the group entitled Apollo and Daphne, a seventeenth century bronze copy smaller than Bernini’s famous marble original. The sculpture represents the moment when the nymph Daphne is transformed into a laurel tree; in this way, according to the ancient myth, the nymph was rescued from Apollo who was enamoured of her.

Rooms 233-235 contain an exhibition of seventeenth and eighteenth century Italian art. In room 233 there are works by representatives of the Genoese school of Baroque painting – Strozzi, Mag-nasco, Castiglioni and others; in room 234 there are paintings of the Neapolitan school, while room 235 contains works by artists of different schools – Crespi, Panini, Rotari, Torelli, etc. Eighteenth century Venetian painting is presented in rooms 236 and 238. Three paintings- Landscape, Town Scene, and View of a Square with a Palace-are excellent examples of the work of Francesco Guardi (1712- 1793), the celebrated creator of Venetian townscapes, full of light and air. A prominent place among the Venetian artists belongs to the brilliant pastellist Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757), whose work is displayed in room 236.

Exhibited in room 238, the so-called Top-lighted Hall, are some large seventeenth and eighteenth century decorative paintings which once adorned palaces and churches. One of the leading artists of Italian Baroque was the Neapolitan Salvator Rosa (1615- 1673), painter and etcher, the author of several paintings diverse in theme, imbued with great feeling, and pervaded with a romanticism of their own (The Prodigal, Democritus and Prothagoras and Odysseus and Nausicaa; in room 234 is his Portrait of a Man, the so-called Portrait of a Bandit). Another Neapolitan painter, Luca Giordano (1632-1705), nicknamed Luca Fa Presto (“Paint quickly”, from the alleged habit of his father in urging ever greater speed), enjoyed great popularity both in Italy and abroad. His work is represented in the exhibition by some excellent canvases: The Forge of Vulcan, The Centaurs’ Fight with the Lapithae and The Dream of Bacchus. The Bolognese painter Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1664^1747) achieved great expressiveness in his paintings by a skilful use of light and shade contrasts (see in room 235 his In the Cellar, Washerwoman, Woman Looking for Fleas and Self-portrait, one of his best works). Also characteristic of Crespi’s painting is the dramatic Death of Joseph, in which a realistic interpretation of the event is combined with a certain tinge of mysticism (room 238). The full bloom of Venetian decorative painting in the eighteenth century is associated with the name of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770). Of the six large-scale canvases in the Hermitage collection five were painted by the artist for the Dolphino Palace in Venice, on themes from ancient Roman history – Fabius Maximus Qulntus in the Senate at Carthage, Coriolanus at the Walls of Rome, Mucius Scaevola before Porsenna, Cincinnatus Is Invited to Become Dictator and The Triumph of the Emperor. These works display the special features of Tiepolo’s painting,- his inexhaustible imagination, brilliant mastery of composition, and bold decorative sweep. In eighteenth century Venetian art there developed the genre of the veduta or townscape, the leading exponents of which were Antonio Canale (1697-1768), known as Canaletto, and Michele Ma-rieschi (1710-1743). In his painting the Reception of the French Ambassador in Venice Canaletto commemorated a festive occasion in the life of his native city. Marieschi presents the everyday life of Venice – the old Rialto bridge with the little shops, the boats on the Grand Canal, bales of merchandise on the embankment, and lines of washing hanging out of the windows. The views painted by these artists, animated by the figures of people, reproduce the radiant, humid air, the uniqueness, and architectural beauty of the “pearl of the Adriatic”.

In the centre of the room stands the decorative sculpture entitled The Death of Adonis by Giuseppe Mazzuola (1644-1725). According to the myth, Adonis, the beloved of Venus, was torn to pieces by a wild boar while on a hunt. Here the sculptor skilfully conveys the turbulent movement, representing the moment when the frenzied beast attacks the youth. The sensation of vigour and energy is intensified by the brilliant working of the marble, calculated to reveal the play of light and shade.

In the second half of the eighteenth century Baroque was succeeded by Neoclassicism, which proclaimed the doctrine of unqualified adherence to antique exemplars. The main representative of Neoclassicism in Rome was Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787); his Hercules between Love and Wisdom is remarkable for the freshness of the colours and the calm grace of movement.

The Top-lighted Hall and the adjoining rooms are decorated with vases, candelabra and table tops made by Russian craftsmen (see page 33).

Room 241 is devoted to the history of ancient painting. Its walls are adorned with large decorative panels which reproduce the development of ancient Greek painting as it suggested itself to the imagination of the nineteenth century artist on the basis of descriptions by the writers of antiquity. The panels were painted in encaustic on copper plates by the German artist Hiltensperger (1806- 1890). The room contains a large collection of works by the leading figure in Italian classical sculpture, Antonio Canova (1757-1822)- Orpheus, Cupid, Cupid’s Kiss, Hebe and Paris. Also here is the work of another well-known sculptor of the Neoclassical school,- the Dane Bertel Thorwaldsen (1770-1844), including Shepherd, Cupid with a Lyre and Portrait of the Countess Osterman-Tolstaya.