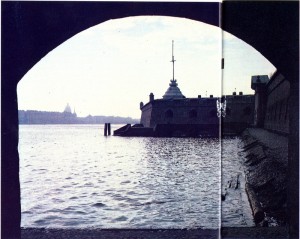

From the very beginning of its existence, the fortress maintained for more than 200 years, besides the above-mentioned functions, yet another one, that of a prison. A study of the fortress prison records shows that major criminals were kept here on several occasions.

For example, in 1715 the main criminal investigation office, located in the fortress, led the investigation of a group of bribe-takers and embezzlers of state property, the head of which turned out to be the St Petersburg Vice-Governor Yakov Korsakov. The fortress also served more than once as a military prison. In 1820 soldiers from the Semionovsky Regiment were imprisoned here. They had protested the inhuman treatment of their regimental commander, and after that still other soldiers arrived from the same regiment who had stood up for their arrested comrades. Beginning in the 1910s the fortress was used almost exclusively as a military prison. In 1916 the Minister of War, Vladimir Sukhom-linov, was accused of treason and held here. But, for the most part, in pre-revolutionary times the fortress served as a political prison. As early as 1721 the Holstein nobleman Friedrich Wilhelm Berkholz, author of a most interesting diary containing valuable information about the St Petersburg of Peter I’s time, upon seeing the St Petersburg Fortress, was reminded of the Paris Bastille, which from the mid-seventeenth century was used exclusively as a prison for political opponents of the kings. Berkholz knew well that in the St Petersburg Fortress “all state criminals are held and often tortures are carried out in secret.”

In 1718 the fortress was the centre for the investigation of the adherents of Peter’s son, Prince Alexei, who had long been in conflict with his father. Deprived by Peter of all rights to the Russian throne, in the summer of the same year Alexei was thrown into Petersburg to Moscow. He was sentenced to ten years of exile in Siberia. The Empress Catherine II led the investigation personally in the matter of the author and publisher of A Journey, even though she, in the beginning of her reign, had demonstrated the intent of acting on humane principles in regard to her fellow countrymen when she had recommended sending a group of students abroad, among them Alexander Radishchev, to study “Natural and Social Law”. On December 14, 1825, the first anti-governmental army uprising in Russian history took place in St Petersburg. Its leaders were intent on abolishing the Tsar’s autocracy. From this day on the history of the revolutionary movement in Russia began, a movement which reached its culmination ith the victory of the October Socialist Revolution in 1917. And from this day on, the St Petersburg Fortress became the place where the most determined and most consistent opponents of the Tsarist regime were imprisoned. Besides the casemates in the fortress walls, another two special prison buildings were used for this purpose built in the Alexei Ravelin and in the Trubetskoi Bastion.

Until well into the year 1826 the fortress was the place of mass detainment of participants of the brutally crushed uprising of December 14. Five of the leaders were hung (on the kron-werk rampart). In 1849 the fortress became a prison for participants of the regular meetings (“Fridays”) which had taken place starting in 1845 at the home of the translator of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mikhail Butashevich-Petrashevsky (they are also known as the Petrashevsky Circle). The members of the circle were arrested for their criticism at these meetings of the present Russian political regime. Beginning in the 1860s members of different secret revolutionary organizations were held in the fortress — “Earth and Will” (in 1863), “The Organization” and “Hell” (in 1866), and “The People’s Will” (in 1881). “The People’s Will”, formed in 1879, was the main Russian revolutionary organization created by the raznochintsy, intellectuals not belonging to the gentry. The group’s main task was the political battle against autocracy; its main ideas were the calling of a constituent assembly, instituting of general voting rights, providing in Russia for the freedoms of speech, conscience, press and assembly. However, to achieve its goals “The People’s Will” chose the erroneous methods of terror. The culmination of the terrorist activities of the group was the as-sasination in St Petersburg of the Emperor Alexander II on March 1, 1881, after which began the routing of the organization by the government. In 1887 members of the “Terrorist faction of ‘The People’s Will’ party” were arrested in preparation to assassinate the Emperor Alexander III and brought to the fortress. Following their trial, five of the members, including the creator of the faction’s platform, Alexander Ulyanov, the older brother of Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin), were executed in Schliisselburg. Lenin thus evaluated the activities of the group: “They doubtlessly contributed — directly or indirectly — to the subsequent revolutionary education of the Russian peole. But they did not, and could not, achieve their immediate aim of generating a people’s revolution.”

In 1896—97 there were more arrests: members of the group organized in 1895 in St Petersburg by Lenin known as the Union of the Struggle for the Freeing of the Working Class, the first proletarian Marxist revolutionary organization in Russia and direct forerunner of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party (RSDWP). And from 1898 to 1904 major activists of the RSDWP were confined in the fortress, along with those united around the first Russian Marxist newspaper hkra (Spark) founded by Lenin, which was printed illegally in Munich, London and Geneva, and was illegally distributed in Russia. After the event which became the direct impetus for the First Russian Revolution, i.e., the shooting of a peaceful workers’ demonstration in front of the Winter Palace (the Tsar’s main residence) on January 9, 1905, the fortress prison was overrun with protesters of this bloody act of the Tsar. “Years passed one after the other,” wrote P. Polivanov, one of the fortress prisoners, a member of “The People’s Will” group, “whole generations have changed, the thoughts and feelings which influenced society have changed, the victims have changed, the executioners have changed; but the Peter and Paul Fortress remains unchanged, ever gloomy, ever ominous, ever willing to take into its casemates victims of tyranny and ignorance. What a terrible picture it would be if it were possible to collect into one all of the horrors which were committed in this Russian Bastille since the first days of its existence!.. So many grand plans, so many broken hopes, so many bright ideas and feelings have been buried within the walls of the various bastions, curtain walls, and ravelins of this fortress.” Indeed, among the prisoners in the fortress not a few ended their days here; among them were those who lost their minds; there were also those whom fear drove to betrayal and desertion. But the majority of the political prisoners stubbornly withstood all of the horrors of solitary confinement, all of the torments by their investigators and rison guards, and when set free, continued their struggle against the monarchy.