As reported on July 22, 1705, in the Moscow newspaper Vedomosti, on May 16 in Vyborg a captured Russian captain “alleged that the St Petersburg Fortress was well fortified and could therefore be regarded as the main fortress.” In June the Swedish Lieutenant-General Georg Johan Maydell made an attempt to seize the fortress from the north.

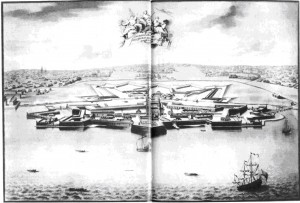

Although this attempt was successfully repulsed, it was decided to additionally reinforce the northern side of the St Petersburg Fortress. For this purpose from 1705 to 1708 on St Petersburg Island, opposite the Golovkin Bastion, an earthen sod-covered fortification, called kronwerk, was erected with an artificial protective slope, glacis, around it.

In connection with the construction of the kronwerk, the Neva channel, which divided “het Mooiste Lust Eiland” from St Petersburg Island, received the name of Kronwerk Strait. In 1706, in efforts to further reinforce the citadel, work was begun on its complete reconstruction in stone starting with its northern side, the approaches to which were the most vulnerable. The reconstruction was directed by the architect Domenico Trezzini, a Swiss-Italian who started to work in St Petersburg in 1703 along with many other foreign architects and engineers. For the new city, which was destined to become the embodiment of the new Russia, Trezzini drew up plans for numerous palaces, churches, buildings for various organizations and private homes, and nearly all of these projects were actually realized.

On May 3, 1706, work commenced on the stone Menshikov Bastion. But after a mere two and a half months, work was unexpectedly halted: on July 18 fire broke out in the fortress.

Miraculously, the fortress escaped irreparable damage; the fire was brought under control before reaching the main powder supply, which was held in wooden casemates within

its earthen walls. Otherwise, the entire fortress would have gone up in smoke. By the end of that building season, workers had succeeded in replacing only the left flank and orillon in stone.

In the following year, 1707, the left flank and the orillon of the Golovkin Bastion, as well as the right flank along with the orillon of the Zotov Bastion were reconstructed in stone. In the same year Peter the Great ordered the main gate of the fortress, which was located in the curtain wall joining the Tsar and Menshikov Bastions, be formally decorated. In 1708 work was undertaken to rebuild the Trubetskoi Bastion in stone. However, once again, at the end of August, all construction work was halted: the Swedish cavalry, under the command of General-Major Georg Lybecker, was advancing on St Petersburg.

Having successfully crossed the Neva approximately twenty miles above its delta, Lybecker intended to attack the city from the south. For several weeks the fortress maintained full battle alert, all of the available supplies of grain in the vicinity having been hauled into it. To the south of the Neva additional fortifications were hastily built. But once again the Swedes’ approach was thwarted.

In June 1709 the Poltava Battle took place, and in June 1710 Russian forces successfully completed the most difficult operation of the Northern War — the siege of Vyborg. Afterwards Peter the Great announced that thanks to taking possession of Vyborg the fortress and city on the Neva delta were finally guaranteed their safety. But at that time these were nothing more than encouraging words. There remained not a few battles to be fought before attaining total security. In the next year, 1711, rebuilding of the fortress in stone was resumed with the next bastion in line, the Tsar Bastion.

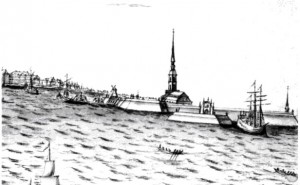

In actual fact only after July 1714 when the Russian forces won their first major naval victory of the Northern War near the Hango (today Hanko) Peninsula at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland, two days after which they took the Nyslott fortress (Savonlinna), the last stronghold of the Swedes in southern Finland — only then could Peter the Great feel truly secure in his position on the banks of the Neva. (And it is no coincidence that the first triumphal arches were erected in St Petersburg only in the summer of that year.) Beginning at this time the main emphasis was switched from rebuilding the bastions and curtain walls of the fortress to finishing, according to the plans of the architect Trezzini, the new stone Cathedral of Sts Peter and Paul, the construction of which had begun in 1712. At this time Peter required above all “that an allotment be made for a clock in the bell-tower.” In 1717 work was begun on aesthetic improvements of the main gate of the fortress. The gate received the name of St Peter, after the statue of the Apostle Peter which was installed above it; and the curtain wall in which the gate was located also received the name of St Peter.

On September 4, 1721, precisely at noon, twenty-one cannon shots rang out from the

walls of the fortress; and at three p.m. in the company of two trumpeters, a kettle-drummer and six grenadiers, a guard-lieutenant drove out of the St Peter Gate holding a white banner which bore two laurel branches under a wreath. They announced to the people of St Petersburg the end of the twenty-one-year Northern War. With the signing of the Nystad Peace treaty the Neva delta and surrounding territories were formally returned to Russia.

Now there was less impetus than ever to reinforce the St Petersburg Fortress. Only as late as June 1725 work was undertaken to rebuild the sixth and final Naryshkin Bastion. At this time the bastion was renamed, becoming the St Catherine Bastion, insofar as Russia was ruled already by Peter I’s widow, the Empress Catherine I; still later the bastion was named the Empress Catherine Bastion. At the same time the Tsar Bastion also received a new name becoming the Peter I Bastion. The raising of stone walls was resumed only after Peter II replaced Catherine I on the throne in 1727. To oversee this process, the eminent statesman, military engineer Burehard Christoph von Miinnich was appointed Head Director of Fortifications. When Peter II moved to Moscow in connection with his impending coronation, Miinnich received “directorship” over St Petersburg and the entire St Petersburg Province. Under his leadership the construction of the Zotov Bastion was finished in 1728, and in 1729 the Peter II Bastion (formerly the Menshikov Bastion) was completed. In 1730 workers set out to finish the Golovkin Bastion, which had been renamed the “St Anne Bastion” (in honour of the saint after whom the new Empress Anna was named, succeeding Peter II to the throne in the same year); later the bastion was renamed the Empress Anna Bastion. During reconstruction of the fortress, the irregularly-shaped hexagon, whose corners were made up of the salient angles of the bastions, became somewhat wider at its east-west axis. In the reconstructed bastions the faces consisted of two brick walls, the space between which was filled with earth; by contrast the flanks consisted of two brick walls with casemates arranged on two floors between them.

In three of the six reconstructed curtain walls there appeared new fortress gates: The Vasilyevsky (Basil) Island Gate in the curtain wall between the Trubetskoi and Zotov Bastions (named the Vasilyevsky Island Curtain Wall), the Second Kronwerk Gate (later St Nicholas Gate) in the curtain wall between the Zotov Bastion and St Anne Bastion (named the St Nicholas Curtain Wall), and the First Kronwerk Gate (later the Kronwerk Gate) in the curtain wall between the St Anne and Peter II Bastions (named the Kronwerk Curtain Wall).

In 1731 reconstruction began of the ravelin covering the St Peter Curtain Wall, which was called the St John Ravelin (the name of the saint after whom the Empress Anna’s father had been named). The gate in the left face of this ravelin was also rebuilt and renamed the St John Gate. Next to the ravelin two stone half-counterguards were erected, which were connected to the ravelin by traverses. The transversal moat, which had been dug back in 1703, was closed off at the ends near the salient angles of the Peter I Bastion and the Peter II Bastion by two ba-tardeaus.

In 1733 construction began of the St Alexei Ravelin (the Empress Anna’s grandfather had been named after this saint). The stone ravelin, with gates in both faces, protected the Vasilyevsky Island Curtain Wall. Two stone half-counterguards were erected nearby and were linked with the ravelin by means of traverses.

Another ditch was dug across the island. It was covered at the salient angles of the Trubetskoi and Zotov Bastions by two more batardeaus. Much later, in 1800, a passage was cut in the batardeau at the salient angle of the Zotov Bastion.

The outside walls of the reconstructed fortress were whitewashed with lime mixed with dark red crushed brick.

In 1731 reconstruction began of the cavalier within the St Anne Bastion (the cavalier was encircled with ditches, which were filled in 1812), and a stone tower was built above the St Catherine Bastion with a flagstaff on top. In 1738 reconstruction began of the bridge leading from the St John Ravelin to St Petersburg Island. The stone drawbridge with wooden central parts was named the St Peter Bridge.

Even before the reconstruction of the entire fortress was complete in 1740 (except for the kronwerk), the afore-mentioned Jacques Savary des Bruslons wrote in his Dictionnaire universel de commerce that, in the opinion of many, the St Petersburg Fortress is second to none in terms of its strength including the world-famous fortress of Dunkerque in northern France.

In 1748 the opening in the curtain wall between the Peter I and St Catherine Bastions was converted to a gate (this became the Neva Gate and the Neva Curtain Wall), and the Neva facade of the fortress was whitewashed with lime. In 1751 brick ramps were built, with casemates inside, leading up to the bastions.

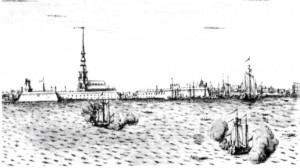

In 1752 Abram Gannibal, a native African sent in his youth by Peter the Great to France to study engineering, was appointed Director of the Building Section of the Engineering Department in St Petersburg. Gannibal was the matriarchal great-grandfather of the famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, who described the former in his short story The Moor of Peter the Great. Gannibal led work on various portions of the St Petersburg Fortress without making major structural changes. Under his direction reconstruction of the earthen kronwerk was begun to provide it a stone foundation. In 1756 the fortifications of the kronwerk were partially faced with brick, and in the period of 1760—74 they were reveted with stone slabs. As regards the fortification of the fortress proper (the structures located on Fortress Island itself), in 1756, according to Abram Gannibal’s plan, portions of the walls were partially faced with stone slabs, and in 1760 plans were drawn up for the “dressing” of the fortress walls along the Neva River in granite. In 1764, at the decree of the Empress Catherine II, work began on facing the Admiralty side of St Petersburg bordering the Neva with granite slabs, since that part of the city had become central. In order to give the Neva facade of the St Petersburg Fortress a no less splendid look, in 1779, at the personal order of the Empress, work was begun to revet it in granite as well. In 1790, with the addition of eleven small towers at the corners on the walls along the Neva, the “dressing” of the fortress facade in granite was complete. This “dressing” served almost no defence purpose whatsoever. By 1808, when the last Russian-Swedish war broke out, the St Petersburg Fortress was ready to repulse any enemy. However, the war ended rather quickly with the signing on September 5, 1809, in the. Finnish city of Fredrikshamn (today Hamina) of a Russian-Swedish peace treaty which has been observed by both sides for almost 180 years now. This treaty was of major significance for Finland: with it Finland began its transformation from a Swedish colony into an independent nation.